Former Georgia Tech quarterback and developer of Charleston’s only midcentury modern hotel, John Dewberry, reminisces about the early days of Dewberry Capital, the life lessons he learned from football, and renovating his historic downtown home.

As a graduate of the College of Charleston, I spent my formative years walking and biking every inch of downtown Charleston, from Battery Park to the streets around Wagener Terrace. In all that time, I rarely gave much thought to the old building that seemed to loom over my favorite warm-weather study spot in Marion Square. But John Dewberry’s creative mind and tenacious spirit had an entirely different view of the L. Mendel Rivers Federal Building, when, in 2008, he bought it from the federal government. He didn’t care that its sixties-era walls were filled with asbestos, or that people in the community claimed he paid too much for an ugly, dilapidated structure. Nor did he listen when they encouraged him to tear down the eyesore. To hear him tell the story as he relaxes in the Music Room of his home on Meeting Street, a cigar in his hand and his dog, Georgia, snoozing away on the antique Knoll sofa, it’s hard to see the business mogul. But his confidence and competitive nature are clear in the results of his business practices. “I’ll be the first to tell you what’s what,” he says with a sly smile. “It’s the quarterback in me. But it’s not about your ego or mine, it’s about what’s best for the project, playing your best, and being who you are.” That phrase, “Be who you are,” is one of John’s main mantras in life. And for a good reason. It was the solid advice his father gave him as an athletic leader and it has translated into success as he morphed into a leader in development and real estate across the southeast.

{For extra pictures of John’s beautiful home and new hotel not seen in the magazine, check out the gallery at the bottom of the blog!}

You began working in the financial industry, so to speak, at Marine Midland Bank after college. What made you decide to change lanes from banking to real estate and development?

I always intended to make the move. Before I was working at Marine Midland Bank, I met with a lot of Atlanta’s real estate leaders and asked each of them what was the most important thing to understand about their industry. Many said if you understand the finance, if you understand the numbers, then everything else falls into place. So I sought a banking job, landed at Marine Midland Bank (which is now Hong Kong Shanghai Bank), and learned everything I could about lending and borrowing money. About 36 months later, the recession of 1990 hit the market. For the real estate industry, it was a very similar recession to the one in 2008. Basically, I experienced a ten-year economic cycle in about three years. This has proved to be a very valuable learning experience.

When did you decide to break out on your own to start Dewberry Capital?

Just before the recession of 1990, in March of 1989, I realized that I could do on my own what I was doing for the developers who came into thebank. So I started Dewberry Capital and started arranging financing for guys who were in dire financial straits. For leaving a safe haven at the bank, people looked at me like I was nuts. But I had learned how to both borrow and lend money, which is more difficult, but brings more benefits in the end.

Clearly that set a great foundation for all that you’ve accomplished up to the present day. What did you study at Georgia Tech that led you into the real estate and development industry to begin?

Georgia Tech is a nerd school, through and through, and I am proud of that.Back then they called my degree Industrial Management, and the curriculum is still very similar now to what it was then. But a Georgia Tech business degree is more quantitative than most schools. I took a lot of calculus, physics, and economic classes for the major. Unfortunately, when I transferred from University of Georgia after my freshman year, the two calculus classes I had already taken didn’t count, so I’m probably the only guy around who had five calculus courses to his name and still can’t tell you much about calculus [laughs].

What Georgia Tech really taught me though, was how to compete. Academics don’t get to take all the credit for that, but I had to study twice, maybe three times, as hard as I was accustomed to make the same level of grades. I woke up at five in the morning to practice throwing footballs, before going to class. But If I didn’t succeed, I was going home. College and football both taught me how to compete to be successful, and my dad taught me how to be just the right balance of confident and humble. Every time I would be too demanding as a leader, Dad would say, ‘Son, you gotta be who you are, but show ‘em your heart and they will follow.’ Dad was right.

While you were the starting quarterback for Georgia Tech, you led the Yellow Jackets to more victories than in the past decade, helped turn around the program, and paved the way for Georgia Tech to move beyond it’s spot among the ten worst football teams rankings. Did you ever think you might play professional football?

At one point, yes. It sounds crazy, but I was probably a better baseball player than I was football player. But I quit baseball when I was fifteen to follow football. When I was younger, I often thought I’d get married and have a family as a pro quarterback. As a baseball player, it’s a lot harder to play 160 games a year, be successful, and have a family. I remember thinking that was two different lifestyles. I just didn’t like the outlook of 160 pro baseball games a year. Plus I loved the position of quarterback. The elements of using the brain, the problem solving, the leadership, all coupled with the athleticism involved in the role of a quarterback were right up my alley. Baseball couldn’t really offer me an equivalent position.

When I got to Georgia Tech, though, it was one of those ‘what have I done’ moments because Georgia Tech was ranked as one of the top ten worst college football teams and I had just left UGA, which recently claimed a national championship. Plus the classwork was much more demanding. So through hard work, perseverance, and leadership, we turned things around; it was probably the first major example in my life of taking a risk, but I knew it was worth it.

After college, I was drafted by Calgary in the Canadian Football League. Quickly, I knew pro football wasn’t going to take me where I wanted to go. My dad knew it too, because he told me I probably wasn’t good enough to play in the NFL. And that sounds harsh to people who didn’t know him, or how he drove me when I wanted to be driven. He also said, ‘John, you’re going to be better at business than you ever dreamed of being at football.’ He and I both knew that he was right.

You started Dewberry Capital with your own capital, which sounds like a big risk. How did you know that was the career path for you?

The best way to put it is that I don’t know any other way. That’s who I am. As I mentioned earlier, it was my father who pushed me early on to use my brain, all of which eventually led me to take that jump. I’d done something similar before, by transferring from a school with a great football program to a school that could hardly win a game. But I knew it would pay off because I would make it so. Every time I think, ‘What have I gotten myself into,’ my next immediate thought is, ‘We’re going to turn this around.’

I evaluate risk differently than the majority of people, which is what it really boils down to. Combine that with having the confidence in my ability to overcome obstacles. It takes a unique skill set to have both vision and an eye for detail, herd all of the cats, keep a project (at least somewhat) on time, and somewhat on budget. I would say my training as a quarterback helped me be able to communicate my goals and problem solve in a way that has aided many other experiences in my life. Keeping the linemen and the running backs from each other’s throats, while calling and executing plays against 11 defenders bent on our destruction, is a lot like leading the architects, engineers, interior designers, and construction crews while trying to make sure the hotel moves toward completion. Five-star hotel development is more complicated than football, though, and I love most every second of it. [laughs]

Today Dewberry Capital spans from Virginia to Florida. When you first began the company, did you imagine it would be this widespread?

Today Dewberry Capital spans from Virginia to Florida. When you first began the company, did you imagine it would be this widespread?

We could have grown a lot quicker, and be a lot more widespread than we are right now. But I’ve told other people who asked me that question, we’re developing quality not quantity. I’ve always been more interested in the beauty of a development than chasing money. As a result I’ve been very blessed in my financial endeavors, so that helps, too, but at the heart of the matter, we focus on giving back to the communities where we invest. It was something my father impressed on me from day one, and it’s something that I strive for every day. Plus it would be nearly impossible to focus on giving back when you’ve got developments in every state or multiple countries around the world. And I think that’s kind of what God cares about—using the gifts He gives you to the best of your ability.

2008 wasn’t exactly the best year for real estate, and the L. Mendel Rivers building wasn’t exactly pristine, so why did you decide to buy that building in that year?

It all goes back to who I am. I am a risk taker. I have a game plan and it involves taking chances. But the risks I take aren’t as crazy as they may seem to a lot of people. They make sense to me because I evaluate risk with a different skill set than most. If I can renovate a building, if I can save a landmark, then I would rather do that and turn it into a new landmark, so that’s what I’m going to do. I bought the empty federal building at a steep discount to replacement costs, because I knew I could to turn it into a five-star hotel. And the whole time my dad’s words, ‘You gotta be who you are,’ were in my head. So I went for it. And we’ve been supremely blessed in the process. It’s also the reason I named the hotel after my dad. I wouldn’t be where I am today without his love and advice.

What initially drew you to the L. Mendel Rivers building?

For one, I didn’t want to build from the ground up. It would have been too expensive. Some may say that I’m not about doing things the easy way, but the easy way isn’t always the best way. But think about it, what other building in Charleston has almost 200 windows just on the front of the building? It certainly makes for great natural light in the guest rooms.

Secondly, no matter which city Dewberry Capital invests in, it’s vital for us to have the best real estate, and that’s what the federal building is. That’s my business model, so that’s what we do. We always end up being on a corner and we’re usually next to a church, too [laughs], but my dad was a preacher so that’s what I am used to.

Thirdly, I wanted to preserve the midcentury modern building. The L. Mendel Rivers Federal Building is one of the best examples from that time period. And lastly, we’re right in the middle of the development craze that’s moving north from Calhoun Street, and situated on Charleston’s main event venue, Marion Square.

Did you have the same vision for The Dewberry as it has turned out, and if not what was that vision?

Did you have the same vision for The Dewberry as it has turned out, and if not what was that vision?

There were things that I changed or that were suggested to me, but primarily I envisioned a place where folks can come enjoy supper, have a cocktail, celebrate their anniversary, or stay for the weekend. It’s true that my ideas morphed a little over time, but I am very hands-on with our projects. I know what I want and work with my team to turn it into a reality. The Dewberry needed to be a meeting place, a relaxing place, and a tribute to all of the things that make midcentury modern great with a few modern amenities in the mix to bring people back. And I certainly hope that’s what we’ve accomplished.

You certainly have. And you’ve done the same with your personal home on Meeting Street, which was built in 1770 and was around to witness the British capture Charlestowne. What was your goal for your home?

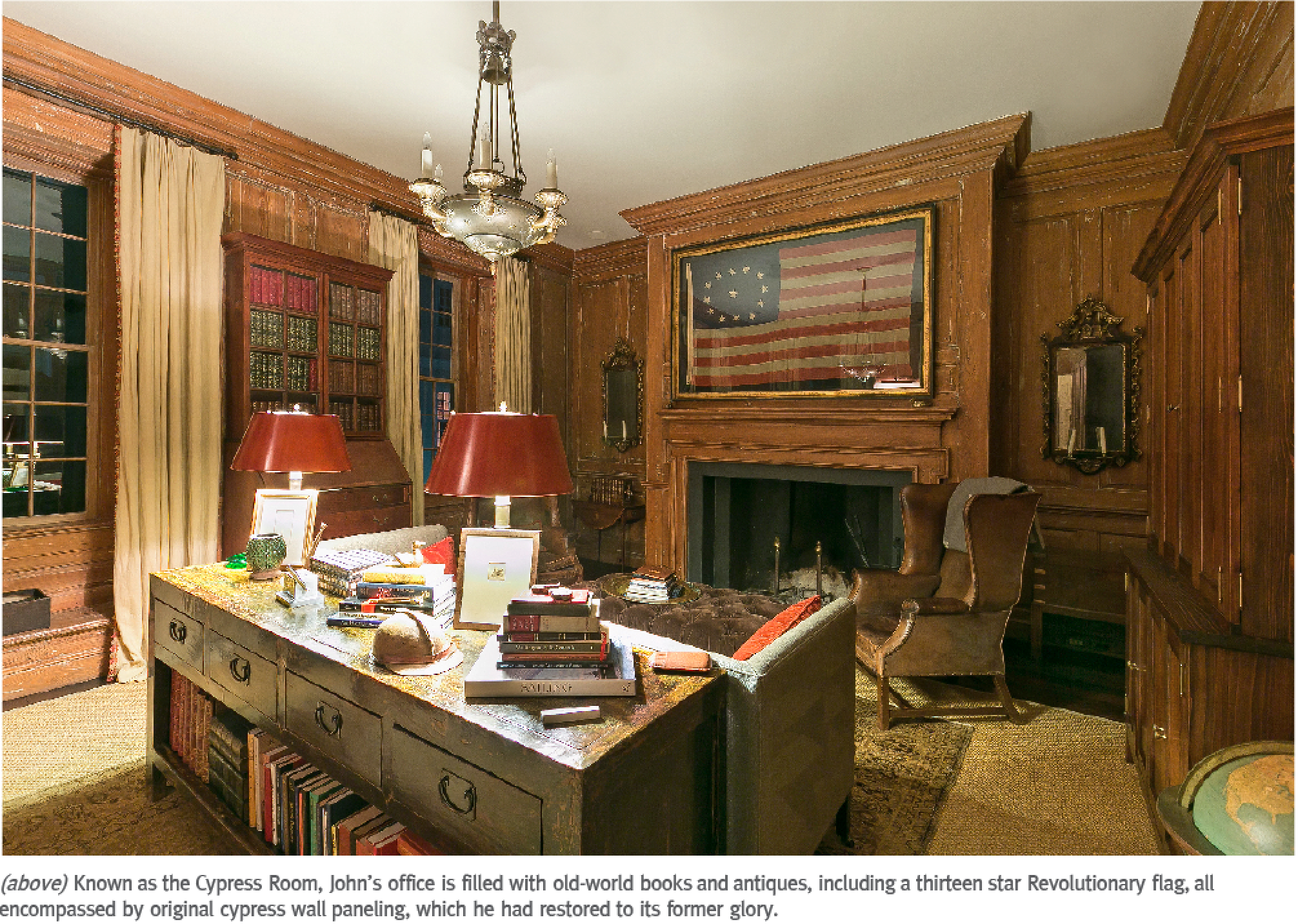

Aesthetically, it needed a serious facelift and at times it’s hard to tell where the old ends and the new begins, which I love. But the most important thing to me was to feel comfortable and to make everyone else comfortable too. The other goal I had was to take the house back to 1770. We pulled up and restored the floors, renewed the structure, refurbished the cypress paneling in my office (which had been painted before I bought the house), and preserved as much of the original Charleston brick as we could.

We raised the second story and then had to raise the windows to match, and we rebuilt every fireplace. It was a true labor of love (most of the time). [laughs]

Once the floors had been lifted and the structural aspects restored, what was the next step in the renovation process?

The kitchen was the most complex part of the whole renovation. It used to be the stables next to the house. A really cool part of the room is some of the tabby on the walls and the brick behind it is 250 years old and some is just thirteen years old. It’s impossible to tell the difference. I love to ask expert renovation guests if they can tell which part is original and which isn’t.

You’ve filled your home with historic art as well. Which pieces are your favorites and why?

I have contemporary pieces like Douglass Balantine’s in the Music Room and the master bathroom, but I think the original Huttys and French artist, Alex Amyé are my favorites. They are so evocative of life and travel and adventure. Plus Alfred Hutty used to live right up Tradd Street. We have two Ridleys as well, which are hunting scenes, and I’m not huge into hunting art, but these paintings are special. The old colonial flag over the fireplace is perfect for the Cypress Room, too, because it harkens back to the time period when the house was new and its first inhabitants were living in pre-Revolutionary (and therefore) dangerous times. That kind of history fascinates me—it’s so remarkable to discover who the people were and how they lived in this very place where we’re sitting.

Clearly you’ve put a great deal of effort and care into this house, but you have one or two in other spectacular places, like Ireland, for instance. So would you say this is your primary home, orjust your home away from home?

Clearly you’ve put a great deal of effort and care into this house, but you have one or two in other spectacular places, like Ireland, for instance. So would you say this is your primary home, orjust your home away from home?

It’s my home-home, for sure. My dad, before he passed, could see that I was different when we would come stay here together. He said that I felt more at home here, and he was right. I love every inch of this house, the history, the city, the community, all of it. Jaimie agrees with my dad, too. Whenever we come here she always tells me how great it is to see me relax.

Charleston is obviously more than just a wonderful place to retreat for you two, but it sounds like you’re not finished developing new properties into fabulous hotels. What’s on the horizon for you and Dewberry Capital?

We’re traveling a bit between Charleston and Charlottesville right now (John is originally from this area of Virginia), working on the finishing touches to The Dewberry Charleston and starting design work on our second hotel in Charlottesville, which has a similar background to The Dewberry. It’s been an abandoned building for a while, and like the federal building was, it is a bit of an eyesore. Construction hasn’t quite started yet, so it’s still a bit of an eyesore [laughs], but things are moving forward and it’s all very encouraging.

Story by Erin Forbes | Photography by Patrick Brickman & Colin Voigt